“What are you afraid of?” my business coach, Kim, asked me this week. I’ll explain why in a minute.

What am I afraid of? A thousand possible responses swam into my head, jockeying for position:

Bees.

Wasps.

Yellow jackets.

Let me shortcut this: every flying stinging insect.

Worms. (gross)

Fish who bite, of which there are few, but boy, they are scary. (Worse: those tiny fish who swim up your urethra.)

Guns.

Ghosts.

Woodrow running away.

Jumping out of a plane.

Neediness.

Seeming like a fraud.

Mark Zuckerberg.

Ouija boards.

Not landing my marks.

Dying before I land all my marks.

Cancer.

But then, I could just as easily ask, What am I *not* afraid of?

That list, thankfully, goes on and on, too:

Being vulnerable.

Saying what I think.

Standing up for what I believe in.

Hard conversations.

Listening.

Change.

Uncertainty.

Looking stupid.

Not knowing something.

Saying I was wrong.

Saying I’m sorry.

Learning.

Taking responsibility.

Being alone.

Spiders.

Needles.

Public speaking.

Heights.

Hornets. (this is a joke to make sure you’re still reading. Of course I’m afraid of hornets.)

Sylvia Plath said, “The worst enemy to creativity is self-doubt.”

I wonder.

I learned something important about self-doubt working on the True Stories project a few years back.

I did this project because I wanted to, and because it was timely. Grant and I couldn’t travel for Christmas in 2019, so we spent the month of December working. Christmas Eve, he was at the hospital.

Christmas Eve had me rewriting, editing, formatting, and I kept at that until December 30th, when I published 30 stories about inspiring people I know. In about 40 days, I wrote, edited, proofread, and published the equivalent of a novella.

I was proud of the lift, but I did it because I was driven to, because they all had great stories.

My interview subjects came from many industries: art, entrepreneurship, acting, sex therapy, penis puppetry, law.

One of the few universals I discovered, other than they’re all geniuses, is that they all reported feelings of self-doubt, weakness, moments where all was lost.

Some wrestled huge demons: Addiction, anxiety, health scares, the death of someone close.

This resonated for me.

We know, vaguely, that people have self-doubt. But it was a revelation that people I admired so much struggled just as much as anyone else. Their struggles had informed a decision, forced them into a grapple, brought about change.

Maybe, I told myself at the time, self-doubt is normal. What a relief.

Now I’ll go further.

Maybe self-doubt isn’t normal. Maybe it’s the driving force for the most vibrantly creative and accomplished people among us.

Self-doubt pushes you into discomfort, and then — if you push back — growth.

Enduring and working with the discomfort of self-doubt is not a signal that you’re a normal human, but an exceptional one.

Self-doubt means you question. You’re willing to be wrong. You’re willing to risk looking bad.

You know, I’ve met a handful of people who never seem to experience self-doubt — or if they do, they never, ever talk about it — and I just cannot admire them.

Respect, maybe.

Fear, sometimes.

Avoid? Definitely.

Do people who never experience self-doubt push themselves to become better? How could they? What would even drive them to?

I’m going to come back to the “What are you afraid of” question, but first I want to tell you about my novel.

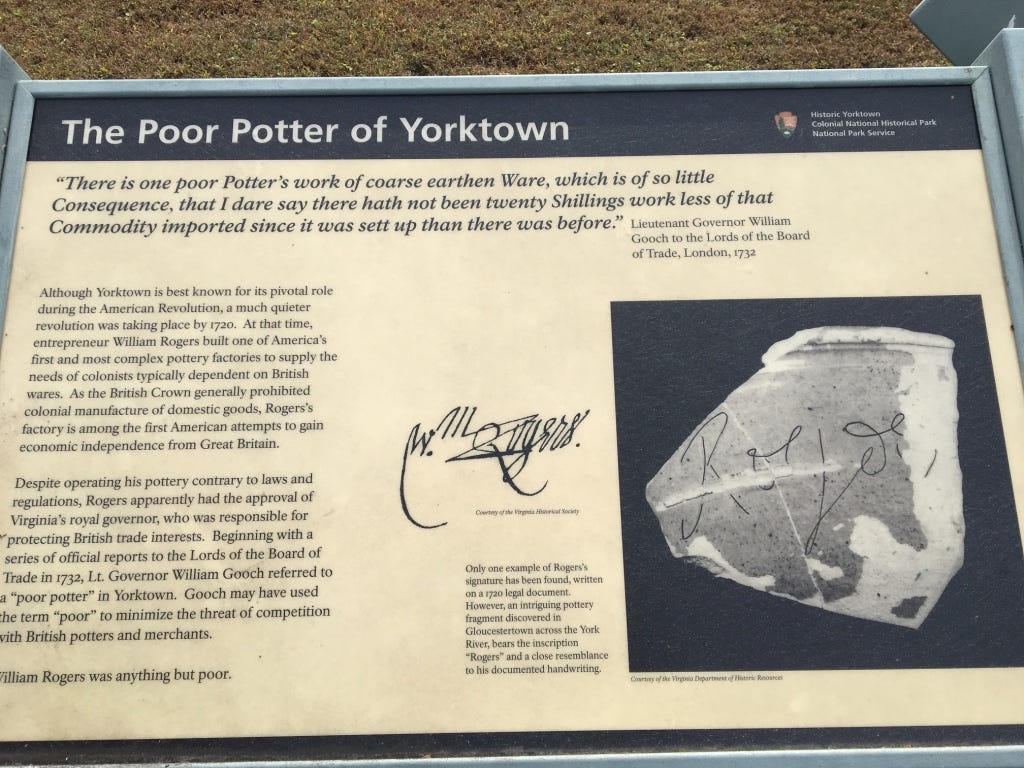

It’s called The Poor Potter: 93,000 words of historical fiction about a merchant who lived in 1720s Yorktown, Virginia, where I grew up.

I grew up in the village where the last major battle of the Revolutionary War was won, surrounded on all sides by houses that look like this:

Speaking of self-doubt. I wrote this book in a state of complete, archetypal Foolishness, knowing zip about pre-Revolutionary America. Ironic, since I grew up completely surrounded by it. Research, a lot of it, was necessary.

EXAMPLE OF A RESEARCH QUESTION:

Q: How long would it take to drive from Yorktown to Williamsburg by horse-and-carriage in 1720?

A: Five hours.

That, multiplied by everything my characters said, did, ate, drank, wore, referenced, or thought, and I’m sure I still got it mostly wrong.

But hey, it’s a book. I wrote it. I experienced doubt and pushed past it. I was bold. I got it done.

I had dinner recently with a friend who read my book last year. She’d had some very kind feedback about it. Kinder still, she offered critique. It’s the mark of a true friend, being willing to go there.

This is a risk every creative takes. When you put work out, someone whose good opinion you care about might say the work isn’t good.

It sucks, but it is a better risk by far than never doing the work at all.

She asked me in a spirit of expecting developments: “So what’s happening with the book now?”

The truth is: Nothing.

But I didn’t care.

I don’t mean “I didn’t care” as in “I don’t care what she thinks.” Of course I care what she thinks. I wouldn’t have shared the book with her if I hadn’t.

It was more of a peaceful not-caring: Trust issues didn’t swarm in and cause me shame or torment about having to expose my underbelly.

This brand of not-caring surprises me. I think a past me would’ve felt my self-doubt, and then run laps to avoid talking about it.

But with The Poor Potter, it truly does not matter. I’m glad I did it, beyond the normal reasons of being glad just to finish something.

My dad, Rogers, was fascinated by the Poor Potter story.

What little we know for a fact about The Poor Potter’s life comes from status reports from Virginia’s governor, who repeatedly lied to superiors in London about whatever was going on with The Poor Potter’s business ventures.

In short: He covered.

Scholars now credit William Rogers with helping pave the way for later economic revolts and throwing off the stranglehold of Britain.

I wanted to answer the mystery of why Governor Gooch (his real name!) (I know!) stuck his neck out to cover for William Rogers and his pottery, and that became my novel.

Having finished four rounds of revisions, I started querying agents in March 2020.

Good timing, right?

But actually.

About the timing.

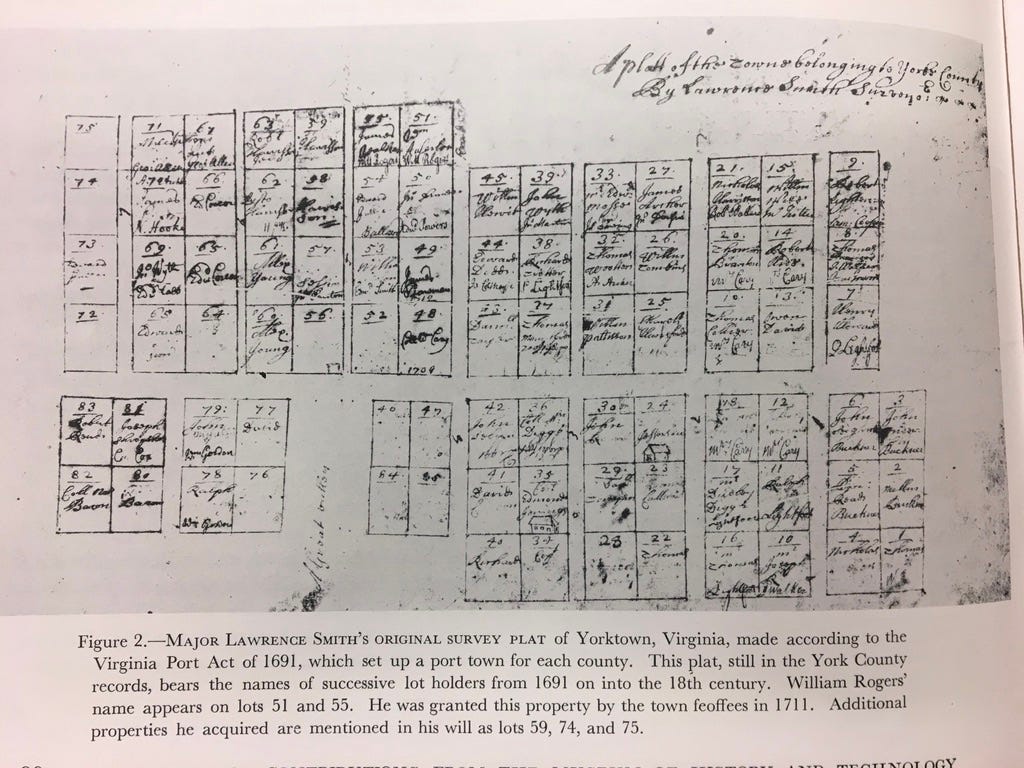

I was interested in The Poor Potter because, as I said, my dad was interested. We both grew up in a house that sits on a property that was owned by “Rogers” — our family, we guess — in 1691.

My dad was also forever saying to me, not as far back as the 1690s but close, “You need to be writing.”

My first year in Canada, trapped here with no job and no immigration status, I legally couldn’t work. My dad said at the time, “You should just be writing. Write. Every day.”

He was right, but I didn’t take his advice, instead spending time a) fretting, b) cooking, and c) playing with our new puppy.

But I started the book eventually.

My parents spent March 2020 reading it. Actually, my mom, in a true labor of love, read the entire thing out loud to my dad. They talked about it over dinner. Sometime in April, we all got to discuss it.

That was one of our last shared experiences as a family.

By May, my dad was hospitalized with pneumonia, and he couldn’t sustain long conversations. Mostly, he slept.

He never recovered, which we now know is because he had stage 4 lung cancer, diagnosed in July.

He died in August.

So finishing the book, that particular book, feels fated. It could not have been more perfectly timed. It was, it is, it always will be, perfect.

You might be tempted to think it a failure if you just looked at the broad-stroke facts, though.

You write a book. I mean, a whole-ass book. You invent it, you spend years creating it, you bleed all over the page, you send it around, and then, what? Nothing happens?!

Nightmare, right?

I had the sense my friend was asking in that spirit.

“Whatever happened with your book?”

“Oh nooooo!”

(sympathetic head tilt, the universal recognition of failure)

I told the truth: I queried 22 agents, got 21 rejections, one request for the full manuscript, and eventually, a 22nd rejection. I planned to query 80 agents, as experts say you’re supposed to, but when my dad got sick, I stopped.

I didn’t plan to stop, I just stopped.

My friend was upset, indignant, at the rejecting agents on my behalf. It was sweet.

But I’m not upset. If it hurt when the first rejection came, I’m certainly not sad now. I lived through 2020. It’s a different ball of wax, sadness. I’m glad to be alive. Glad to be doing work I care about. Glad for the drive to make things. Glad for the lessons of failure.

This part is easy: it’s only demoralizing if I make it so. Every writer talks about their early rejections. The trick here is: Keep going.

I made this book. I’ll make more.

“What are you afraid of?” my business coach, Kim, asked me.

We were talking about a very recent, very this-week fear, which is an inward-shrinking, a strange reticence to launch the website for my new editorial business.

I practice Tim Ferriss’ fear-setting exercise once or twice a year, so I know about interrogating my fears.

I started ambling down familiar paths: “People might judge me,” “They’ll think my website is dumb,” “They’ll think I’m dumb.”

(“Who does she think she is, anyway?”)

(Not Joan Didion.)

(And Prufrock was not Prince Hamlet.)

But I realized: Although those are all well-trodden paths in my head, they’re not true of this venture.

They might not be true at all anymore. I’m still unlearning my lifelong tendency to be externally referenced.

But I can tell you: I’m not as fearful about what other people will think as I am about what I will think.

I’m in competition with myself, the Angela of five years from now, as I imagine her: a slick client-engagement funnel, merch, new branding, refined offerings, everything figured out.

What if she looks back and is embarrassed by the first attempt.

That’s it. That’s the doubt. That’s the fear.

But I’ve trained for this moment. They drilled this during my digital media coursework: Gotta launch before you’re ready. You’ve waited too long if you’re not embarrassed by v1.0.

Still, it’s not like with Quupe, or further back, Supersnack, when I had teams of people around me, when failure was a shared moment of suck.

Now it’s just me. I’m exposed. If it sucks, the only person who sucks is me.

No, but wait.

If the work sucks, I still don’t suck.

It could rain. The sun always comes back. Living in Vancouver teaches you that much beyond any possible doubt.

I am also, even alone, very supported. By Zeeshan. Kim. Monica. Abhi. Mallory. Allison. Rachel. Every person reading this right now.

And Grant, without whom none of this would be possible.

And I’m also supported by my past self (she tried!) and my future self (she keeps trying!).

Kim asked me, “Would your future self really judge you for putting out a first version?”

No, of course. If anything, she’ll be grateful I took a leap. She’d be proud of me for feeling the fear and doing it anyway.

For proof, just witness how I speak about this chick who wrote The Poor Potter two years ago.

And, so, self-doubt?

I’m having self-doubt like all those amazing people I admire so much from my interview project?

Good.

It’s not possible to get wherever I’m going without passing, low and slow, through these way stations first —

uncertain,

feeling small,

so aware of being not-yet-good-enough,

not, in short, perfect.

Well.

So what.

I don’t need to be perfect.

I have self-doubt.

Thank goodness.

I love this, Angela. (And now I feel incredibly guilty that I haven’t read your book yet even though it’s still starred in my inbox because my inbox is a to-do list for me! Last year got very weird, right?) xoxo, keep going.